Part three in my ongoing attempt to blog my way through my MRes thesis. In my previous post I touched upon the association between the photocopier and the office and in this post I’m going to return again to that topic.

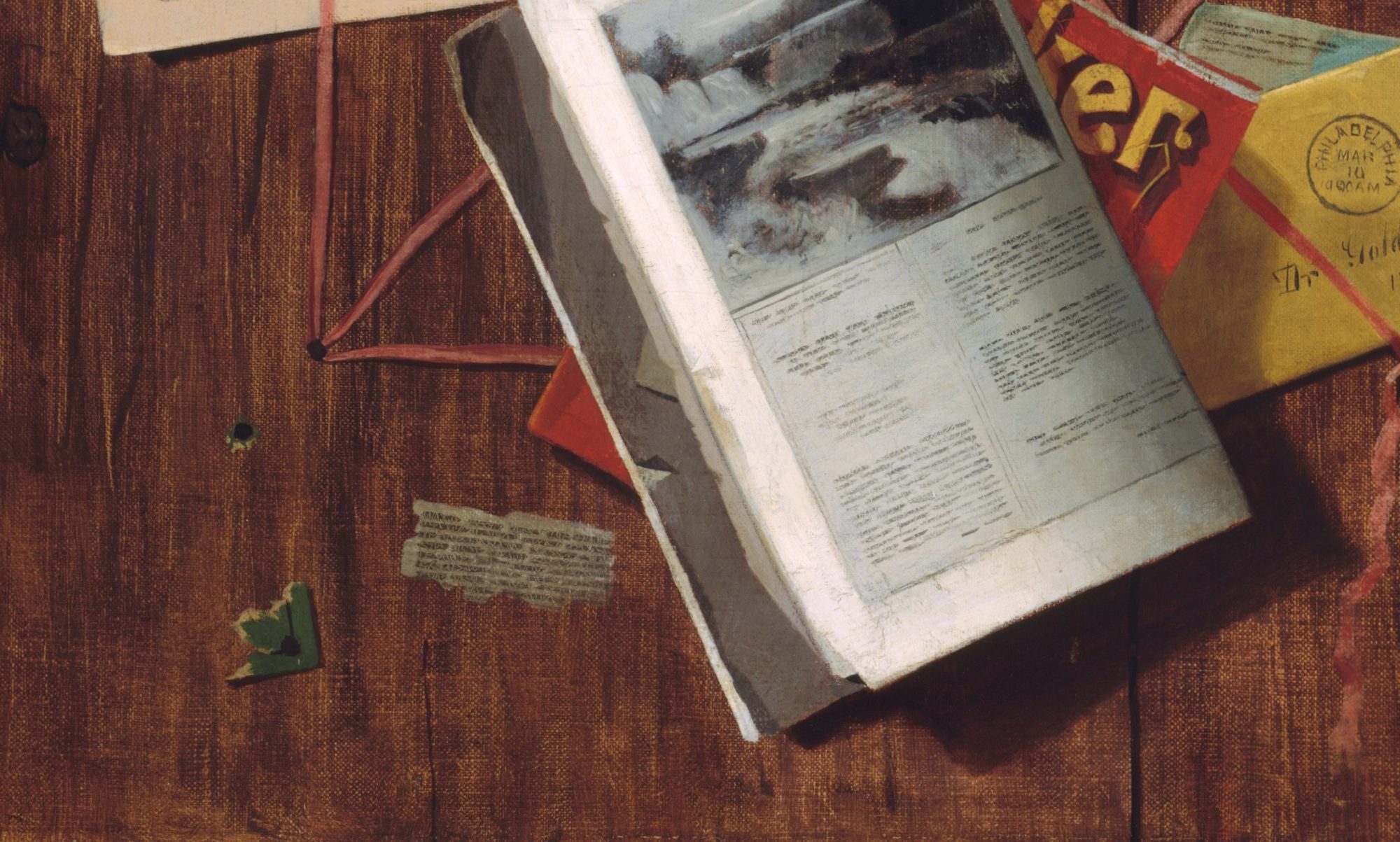

As the office developed through the 19th and 20th centuries so did its association with, and mimicry of the processes of industrialized mass production. The required mass production of information for the success of corporate procedures and processes reflected the mass production of materials and commodities. The office increasingly practiced a form of ‘light manufacturing,’ manufacturing information through standardised and routinised processes and procedures. The photocopier epitomises this functionality, as it is, in reality, a miniature production line. The photocopier uses a combination of raw materials, standardised human labour, and a mechanised process to duplicate information. Minimal human input and standardised materials enable the creation of multiple reproductions of the item placed upon the photocopiers myopic lens.

The mass production of corporate ephemera and bureaucratic paperwork increases the monotheistic pattern of thought and idea, one overriding belief or ideal that governs everything. People can become increasingly isolated through the printed media, a single sheet of information, produced, typed and printed can be reproduced and distributed to all corners of the office to be accepted and obeyed. This monotheistic viewpoint is mediated by the nature of the photocopier as it enables the mass production of the corporate command. People are dissuaded from deviation and personnel interpretation through the narrowness of the printed word. The written, printed, and copied word allows reaction without true involvement, acquiescence to corporate edict.

The operation of office machines, the function of the office production line, creates a high level of specialisation evident in any industrialised factory setting, a process that deskills its workforce. Each individual is responsible for their own task, their own station, unable to complete other tasks than the one proscribed by the employer. We see the production line reflected in office procedures, each individual is appointed to a particular part of the process, dependent upon the person before, and depended on by the next person in the chain. There evolves a high level of specialisation as the individual masters their task, but there is little encouragement to deviate from that task less the production line falter. As Miles Orvell writes,

For the office worker […] interactions with the machine – whether telephone, adding machine, or typewriter – enforced a rhythm or repetition and fine coordination.[i]

There is seemingly a general deskilling wrought by the increased prevalence of the office machine. The photocopier, in enabling the efficient mass production of paperwork, ultimately reduces the need for other more specialised forms of written and printed efforts. The photocopier requires little skill to use, only basic training to understanding and, once the process had begun, the participation on behalf of the operator is minimal. In an interview the artist Mark Pawson, who has had a long standing obsession with the photocopier, assents to its ease of use when said that, ‘once you’d seen someone use it, or had seen someone press 2 or 3 buttons you could kind of work it out for yourself, you didn’t any special training or skills.’[ii] Historically methods of reproducing the printed world have required greater skill and individual participation, hand written manuscripts, type setting, even the hand-cranked mimeograph involved the operator in the process. But the photocopier reduces office participation to a few buttons and leaves the individual largely redundant. In a Guardian article written in 1966 this deskilling is lauded by its author,

The difference now is that no transcription errors are made, preparation time spent by experienced staff is reduced, and the company has fewer employment worries at a time when competent staff is increasingly hard to find and keep.[iii]

While this may have been heralded as beneficial for the corporation, skilled staff found it increasingly difficult to secure work, and available office jobs become less skilled and less well paid. One newspaper report from 1983 highlights the damage done to more traditional print industries by the growth of new technologies such as the photocopier. It reports that in the previous decade the number of people employed as part of the printing industry had declined by 55,000 to 250,000, and that the National Development Office forecast that that number could plunge by another 84,000 to 166,000 due to ‘expanding rival sectors such like word processors and photocopiers.’[iv]

Initially the photocopier was seen as a marvel, a miracle of the modern technological age. Another article from the Guardian newspaper in 1962 hailed it as a ‘space age revolution.’[v] But ultimately familiarity breeds contempt and the photocopier would become an object of disdain. The seeds of this contempt were in place early on in the photocopier’s existence. In an article from The Washington Post in 1964 the photocopier, while trumpeted as an exciting advance, was also characterised as a device requiring little skill to use. In an indication of the period’s attitudes to women, the article relegates the photocopier to the domain of the office secretary, then illustrates it’s easy of use by describing how a monkey had been taught to use it.[vi] The process of using the photocopier would become a demeaning one, a task or job relegated to the least important, someone who needed little training or skill.

The photocopier is a complex combination of environment, experience and interaction, which mediates people’s opinions about this, eventually, mundane office appliance. Marshall McLuhan says that these interactions are part of what form our created environment, and he writes that, ‘Environments are not passive wrappings, but are rather, active processes which are invisible.’[vii] Human experience is never passive, but is involvement in an active environment, environments that are created, constructs that bring with them connotations for all media within them. Unlike the personal computer, which would eventually sever its connection with the workplace as its cost of ownership reached levels obtainable by most households, the photocopier would never sever the ties to its office environment.

[i] Miles Orvell, After the Machines: Visual Arts and The Erasing of Cultural Boundaries (USA, University Press of Mississippi, 1996)

[ii] Pawson, Mark, Interview with Mark Pawson, London, 14 May 2012

[iii] C. Northcote Parkinson, ‘Parkinson’s Law of Delay’, The Guardian, 21 September 1966

[iv] Michael Smith, ‘Jobs ‘At Risk’ In Print Industry’, The Guardian, 02 February 1983

[v] Ritchie Calder, ‘The Space Age Revolution Called Xerography’, The Guardian, 06 November 1962

[vi] ‘The Xerography Boom Echoes Across the Globe’ The Washington Post, 28 December 1964

[vii] Marshal McLuhan, The Medium is the Message (London, Penguin, 2008)