As I find blogging something of a slog I thought a useful way to get started, and to press on might be to take something I’ve previously written and shape it to fit. With this in mind I thought it might not be a such bad thing to start with my MRes thesis. The thesis explored the role of the Xerox machine in the rise of the British Punk youth movement in the 1970s, examining the dual nature of the Xerox machine as a corporate and subcultural entity, and the assumptions and preconceptions surrounding it as a tool for communicating. My plan is to work my way through the thesis editing and shaping as necessary, which will hopefully not only help me to actually keep up blogging but may also help to improve my editing skills, we’ll see if these modest aims can be accomplished.

INTRODUCTION

Marshall McLuhan articulated claimed that the medium used to communicate information effects and constrains how that information is received. He wrote that the, ‘medium […] shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action.’[i] The form of media used to communicate will shape our perception of that communication and the breadth of that communications reach. McLuhan sought to explore the nature of electronic communications and the ways in which they change our environment and shape how we interact and communicate. He believed that electronic technology would force us to re-evaluate and dramatically reassess every aspect of the human environment since, ‘societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media by which men communicate than by the content of the communication.’[ii] Electronic communication, he asserted, would change everything.

The purpose of these subsequent blog posts (once my MRes thesis) is to examine the punk movement, it’s social setting, cultural engagement and creative activities. I will give particular thought to punk’s uses of the photocopier as a means of communication and how that technology influenced the messages that punk sought to convey. I want to begin by grounding both punk and the photocopier firmly in their respective cultural situations before moving on to examine them more closely. The ability to understand both punk’s beginnings, its direction and development, and the photocopier’s corporate, and eventual subversive appropriation are tied to our understanding of their cultural wrappings and environmental influences. Author Harold Osborne argues that,

A work of art is not a material thing but an enduring possibility, often embodied or recorded in a material medium, of a specific set of sensory impressions.[iii]

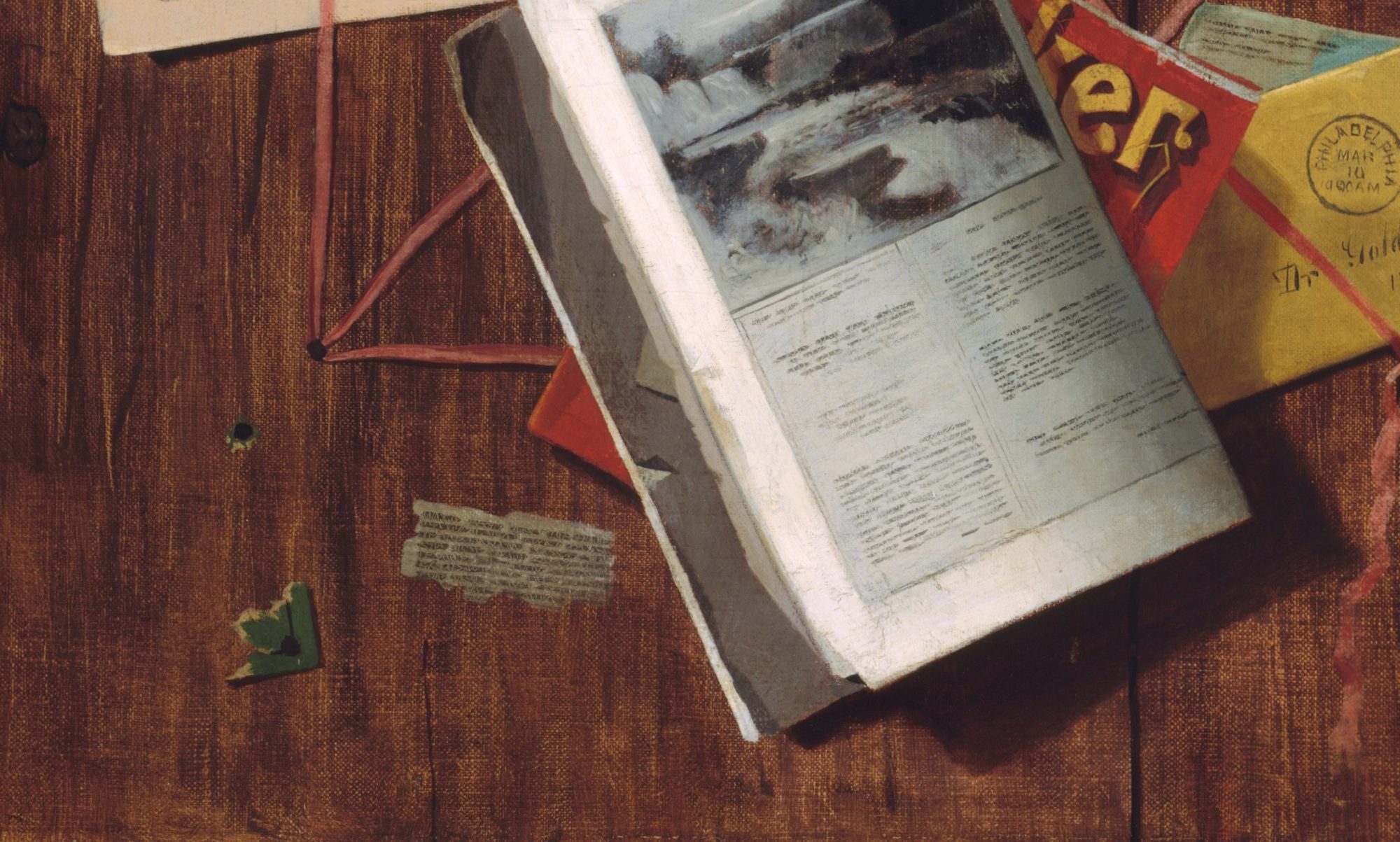

Although Osborne was writing with a focus upon the origins of an artwork and its conception, the idea of an artwork as an enduring possibility and representation of its creators perceived sensory impressions embodies a concept that might be easily be extended to the formation of both youth subcultures and corporate industrial creations. Punks, or the youths that would eventually form the punk subculture, own sensory impressions encompassed the culture and cultural products surrounding them, their own social conditions, perceived frustrations and desires, and lack of opportunity for expression. Similarly, the photocopier is the product of mechanised industry, a commercial commodity dominated by connotations of the corporate. If action, it might be argued, is born of belief, both the photocopier’s creation and punk’s subcultural formation, it could be said, are actions born of the belief, perceptions of their creator’s own environmental circumstance and ideals made manifest. Punks own ‘enduring possibility’ was the zeitgeist of conscious and subconscious subcultural dissatisfaction, rendered into material form, visual and audible. Both punk’s music and its visual arts were reflections, representations and reviews of the individual’s cultural experience. While the Xerographic process, the process underpinning the photocopier, as it was first called and its success was a result of its creator’s ingenuity and perceived need, the Haloid’s Corporation’s drive for financial attainment, and adoption by a corporate culture who desired increased routinisation and systematised of its administrative practices.

In the blog posts that follow I will examine both the photocopiers beginnings, influence and usage in the corporate sphere, and the cultural and environmental conditions that lead to punks formation. I will go on to explore punk’s ideological and historical influences focusing on the three separate and distinct waves that saw punk grow and change from 1976 through to 1984. I will then examine punk’s visual foundations and ideological leanings before looking at three separate entities of punk creative activity, the fanzine, the flyer or poster and the album or single sleeve. These three artefacts encompass the development in punk culture from amateur to increased professionalism, from individual youth action to corporate involvement, and social and political participation. They also highlight punk’s uses of the photocopier, its subversion from its corporate roots and appropriation of this cultural technology, its aesthetic qualities and visual influence and its eventual facilitation of a recognizable punk style, something that could be marketed and reproduced.

This approach should allow me to explore and evaluate punk and the environment it was influenced by, and by extension place the photocopier in the environmental context of its influences, uses and effects on those areas of punk’s visual culture it helped shape and create. The photocopier, its history, particular visual quirks and uses become sensory impressions that shed further light upon punk creations and its uses as a subcultural aid to communication. The photocopier should be recognized as a complicated amalgam of its different cultural and subcultural uses, a combination of corporate assumptions and subversive enablings.

[i] Marshal McLuhan, The Medium is the Message (London, Penguin, 2008) p. 9.

[ii] Marshal McLuhan, The Medium is the Message (London, Penguin, 2008) p. 8

[iii] Osborne, Harold, Theory of Beauty: An Introduction to Aesthetics (New York, Philosophical Library, 1953), p. 202.