Part two in my ongoing attempt to blog my way through my MRes thesis.

Electronic means of communication, such as the photocopier, are surrounded by consciously and subconsciously perceived assumptions. These arise from a host of factors including their manufacture, their function, and their perceived societal role. As McLuhan writes, ‘no medium has its meaning or existence alone.’[i] These assumptions or prejudgements can shape our understanding of, what Bruno Latour might call, their substance, resulting in a misunderstanding of their cultural significance and our interpretation. Subsequently our perception of a method of communication can then shape how we perceive the message communicated. Our perceptions and assumptions of the mode and method of communication influences our perceptions and assumptions of the message, even before the message has been received.

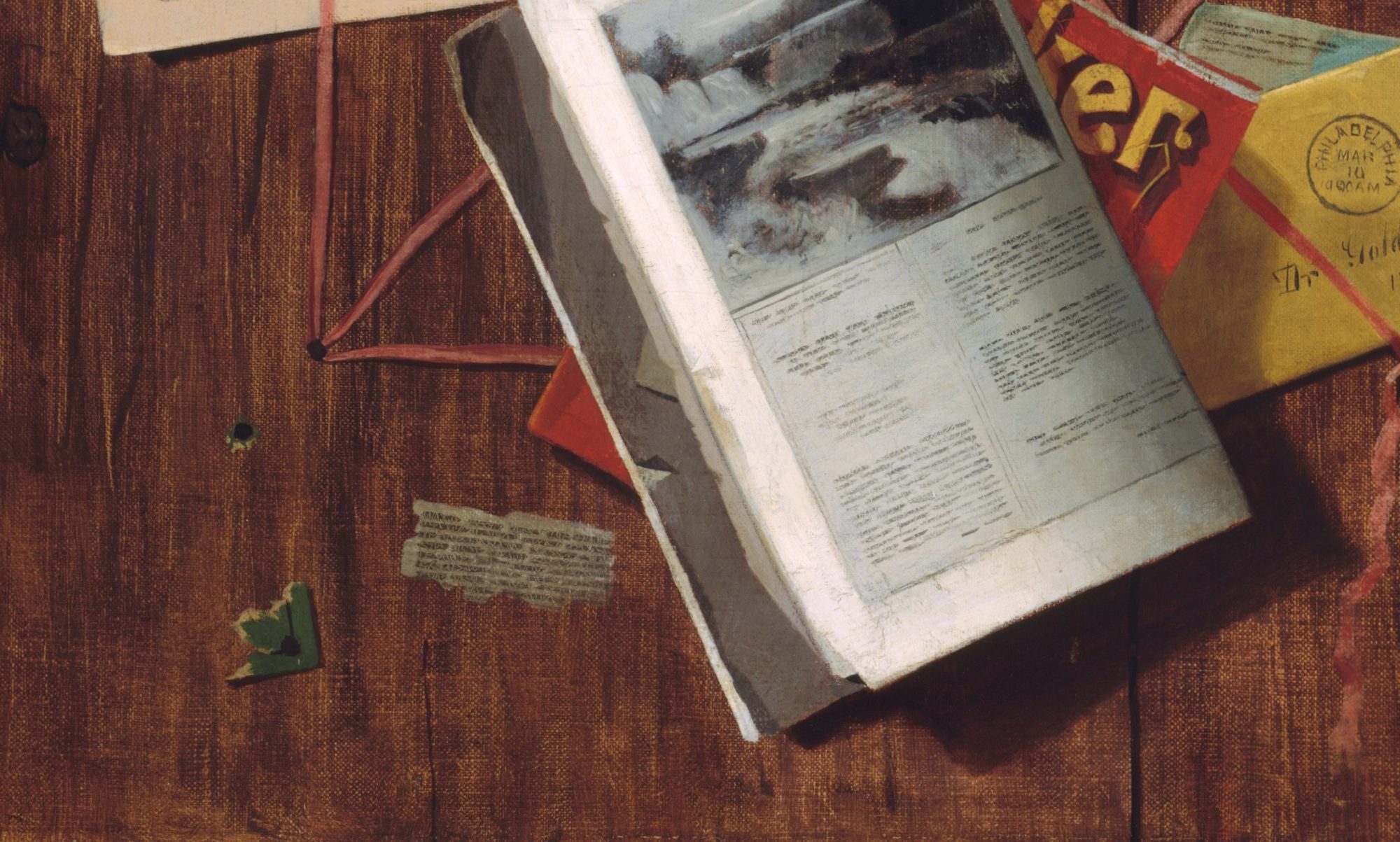

The premise of this blog post is to briefly explore the assumptions that surround the photocopier, by situating it in its historical and theoretical context, with an eye to later discussing its role in the UK’s punk scene of the late 1970s and early 80s. The photocopier is a prime example of a form of electronic communication that is laced with preconceived assumptions and associations. The photocopier may be one of the most presumed upon, mundane, and least glamorous means of communication. In a 2016 BBC news article, Some of the World’s Most Boring Jobs, the image the article has as its header is one of a young woman asleep on top of a photocopier.[ii] The photocopier is largely seen as a banal, functionally bland, and limited means of communication. Anyone who has ever worked in an office has probably had cause to use one, its presence is rarely questioned, its roll assumed, and our assumptions about it well established. But, I would argue the photocopier is actually a complicated, multi-faceted substance, our perception of which is formed by a complex combination of historical situation, corporate association, technological function, and user interaction.

Take for example the Haloid Corporation, the creators of the first office photocopier. The purpose behind creating the photocopier for the company was increased financial revenue. The creation of the photocopier, the corporate reasoning behind its design and creation was financial gain.[iii] The photocopier subsequently becomes an expression of the corporation, a reflection of both its aims and the market it supplied. Its ‘public image’ is initially then a fabrication based upon its associations with the corporate. The process of electrophotography may have been envisaged by a man with altruistic and charitable leanings, but its subsequent licensing and production by the Haloid Company, not to mention the plethora of other companies who would go on to develop and manufacture their own devices using the same process, would make it a creature of this corporate realm.

Subsequently the photocopier would begin to shape the business and bureaucratic world it had been built for. Three years after the introduction of the Xerox 914, the machine that would cement the photocopier as an essential office tool, in 1962 the office copying equipment industry would be worth more than $250,000,000 a year in the US alone, with nearly one-hundred manufacturers involved in the production of xerographic equipment.[iv] Due to the success of the photocopier the Haloid Corporation would eventually change their name to the Xerox Corporation, and would increasingly focus upon the office as a market. So much so that they founded Xerox PARC, ‘an institution originally founded to study, invent and design “the Office of the Future.”’[v] The nature of the Xerox Corporation would become inseparable from the device it created. It would provide for, and influence the nature of what an office was and did. Through this cycle of association and design the photocopier, which had gone some way to shaping the corporate world, would become inextricably linked to it.

The pervasiveness of the photocopier, its role in aiding efficiency and accumulating corporate wealth further cemented the photocopier as a feature of, and facilitator of the corporate. With the rise of office machines such as the photocopier the office would become ever more a reflection of the factory floor, and office procedures a semi-humanised production line. The photocopier would become increasingly associated with corporate banality in the minds of employers and employees alike. The high cost of the photocopier places it beyond the reach of personal ownership and private use. It’s was generally therefore restricted, and individual interactions with it confined to the workplace. Unlike the personal computer, which moved beyond the office, the photocopier would become synonymous with the workplace largely because people’s interactions with it would be mostly restricted to that environment. In a newspaper article in the Observer in 1957 a journalist describes the picture of office life typical of 1950s Britain, an office now seemingly run by ‘smooth grey business machines.’[vi] But, this positive view of these labour saving devices didn’t last. In a newspaper article in 1981 the author highlights the shift from praising the ‘smooth grey office machine’ to lamenting, ‘the generation of pointless paperwork made possible by the photocopier’, which the journalist describes as ‘one of the most unfortunate phenomena of the second half of the century.’[vii] The photocopier, its actions and stylistic quirks would become bound by the drudgery of the corporate or bureaucratic world. Its location within the workplace, and the perceived drudgery of that sphere, would taint subsequent associations and perception.

[i] Marshal McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (London, Routledge, 2009), p. 28.

[ii] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-36902572

[iii] The M.H. Kuhn Company founded in 1903, which later became the Haloid Company in 1906, would originally manufacture and operate as a provider of photographic paper and equipment. After licensing Carlson’s Xerography process in 1948, and with the subsequent developments in Xerographic technology, the direction of the company would increasingly shift towards the production and selling of the Xerox machine. The most obviously evidence of this development is seen in the companies re-branding from the Haloid Company to Haloid Xerox Inc in 1958. Its final re-branding in 1961 would complete the transition as they became the Xerox Corporation; by 1961 xerographic products made up 86.6% of the company’s total corporate revenue. The Xerox Corporation was hailed as one of the most extraordinary business stories of the Twentieth Century, growing one-hundred fold in fifteen years. It was Chester Carlson’s invention that would shape the future of the company and give it its direction for the next sixty years.

[iv] Earnings of Xerox Soar to New Highs’, New York Times, 18 July 1962, p. 35.

[v] Craig Harris, Art and Innovation: the Xerox PARC artist in residence program (Cambridge, The MIT Press, 1999), p. 13.

[vi] John Davy, ‘Getting the Paper Under Control’, The Observer, 16 June 1957, p. 4.

[vii] Hamish McRae, ‘Xerox Will Hardly Do For The Typewriter What It Did For The Photocopier’, The Guardian, 18 November 1981, p. 14.